Profile: Arielle Johnson – Head of Research, MAD

Arielle Johnson manages the research program for MAD in Copenhagen, Denmark. MAD is a non-profit organization founded by chef Rene Redzepi, devoted to improving both the practical and theoretical understanding of food. Arielle entered the food industry with a PhD in flavor chemistry and perception, but her interests and work are wide-ranging, encompassing new techniques for the kitchen and, of course, fermentation management. In her own words, “My role within the organization is to sort through the existing body of scientific knowledge and find things that we can apply to make the creative process more creative.”

What ferments are you excited about at the moment?

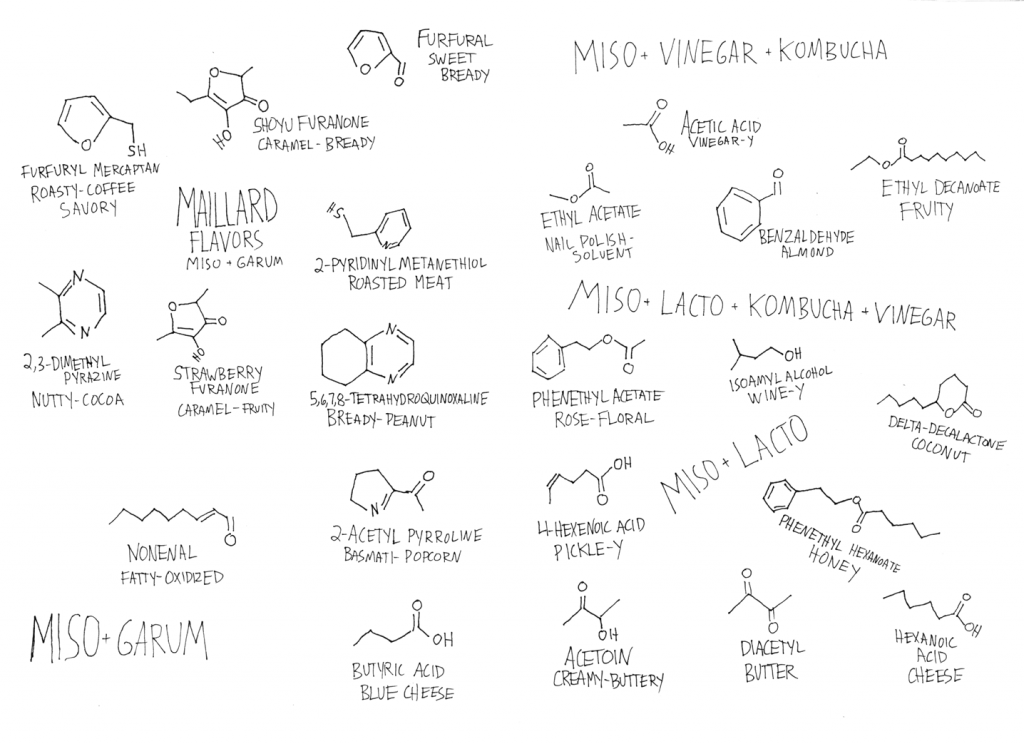

“Pea-so” is our workhorse miso. We grow the koji on barley and then cook peas until they’re fairly soft, and then mix the two together with salt. Japanese people usually don’t ‘get’ our misos because of their high level of lactic acidity. We’ve found that at the same bulk percentage of salt, the water content has a huge effect on the flavor profile. The wetter Pea-so is way more sour. You can tell from tasting that there’s more acidity, and with the scientific knowledge you can put the pieces together and understand why the bacteria are behaving as they are.

Then there is Hazel-so: miso made from hazelnuts. If you try to make whole hazelnut [paste] into miso there’s way too much fat and it starts going rancid. We produce a lot of hazelnut oil at certain times of the year [for sister restaurant, Noma], and when you press hazelnuts, you get oil-free, partially cooked, defatted hazelnut scraps. It’s crazy how fruity it gets when you ferment it! [Its flavor is like tutti-frutti crossed with marzipan and stock cube.] Hazelnut itself has just a very few fruity-creamy aromas, but you don’t get the complete flavor coming through until you get some acidity in there and fruity esters develop from the fermentation. Who’d have thought you could get a flavor like that in Denmark from hazelnuts?

Then there is Hazel-so: miso made from hazelnuts. If you try to make whole hazelnut [paste] into miso there’s way too much fat and it starts going rancid. We produce a lot of hazelnut oil at certain times of the year [for sister restaurant, Noma], and when you press hazelnuts, you get oil-free, partially cooked, defatted hazelnut scraps. It’s crazy how fruity it gets when you ferment it! [Its flavor is like tutti-frutti crossed with marzipan and stock cube.] Hazelnut itself has just a very few fruity-creamy aromas, but you don’t get the complete flavor coming through until you get some acidity in there and fruity esters develop from the fermentation. Who’d have thought you could get a flavor like that in Denmark from hazelnuts?

Do you inoculate your fermentations?

Well, we have spores we buy in for the koji. For our vinegars we make a wine first and we might inoculate with yeast for that, and we keep SCOBYs for our kombucha. For our lactic fermentations we just add salt.

How important is consistency?

It’s important but not paramount. You have to remember that everything is going to get adjusted in the restaurant kitchen. If it’s not good, that’s bad, but we can deal with pretty big variations from batch to batch. But remember, we are looking for new things: we set out with each trial to get something different and new and tasty.

We also have Saturday Night Projects. A few chefs will regularly do a fermentation project, and make something to put on their dish. Recently there was a lot of sea urchin around, and one of them took sea urchin goop and made miso out of that, and it was phenomenal. That’s the coolest thing [about my job]: figuring out the basic biochemical knowledge, that you can then teach to a chef who’s not a scientist so they can start thinking about microbes as a tool that they can use in the kitchen, like a knife or a pan.

To try to formalize this, Lars Williams [head of R&D for Noma] and I wrote a fermentation handbook, which we’re just about to publish. We tried to explain the science as clearly as possible, and I drew some pictures to help illustrate the concepts. We also included question and answer sections for each type of fermentation, not just for troubleshooting, but to explain why some things are possible and others don’t work.

Do you think that more natural fermentations will filter down into normal everyday cookbooks and cooking over time?

I definitely hope that a lot of this will become more widespread. You’re already seeing a lot of people do things with lactic fermentation like sauerkraut, which is great, but maybe not the very most exciting fermented food out there. There’s a lot of creative potential for people to work with things made with koji, like miso. It’s also more technical, so it can be a little intimidating. Grandmothers in Japan make miso at home, so it’s not impossible. With a lot of things like beer and sauerkraut, you can just leave them out on the counter and they do their thing. Having control of temperature and humidity is the most difficult part for the more sensitive fermentations.

What’s your favorite microbe?

It’s hard to pick a favorite, but just for sheer usefulness, Aspergillus oryzae is pretty rad. There are things you can do with plain koji, but enzymatically it’s so useful and versatile that it opens up this world of possibilities. The whole enzymatic architecture it has put in place is really awesome.

Could You tell me when to expect or where to find the handbook?

Hi Tom,

I checked with Arielle and the MAD team have recently decided to publish it more officially, which may take some time. When it’s available, I’ll post an update with details on how to get ahold of it here.

Best wishes,

Bronwen

Hello Lars and MAD team, I would like to ask if your handbook has been published by now or still on the pipeline?

[…] Arielle Johnson is a flavor scientist and head of research at the food think tank, MAD. She’s also the resident scientist at restaurant noma in Copenhagen. Johnson collaborates with chefs, designers, engineers, and other scientists to dismantle the boundary between the kitchen and the laboratory. […]